Trip would be first by a UK prime minister in more than seven years — but there is still a live debate about the Labour government’s “audit” into its China policy.

LONDON — He’s already sent his chancellor and foreign secretary to Beijing, and Foreign Affairs Minister Wang Yi arrives in London Thursday. But one very big step remains in Keir Starmer’s China charm offensive — visiting the country himself.

Downing Street is drawing up plans for Starmer to go to China, in what would mark the first visit by a U.K. prime minister in more than seven years, four people familiar with the U.K.’s position told POLITICO.

Senior officials are in discussions about a trip some time after this summer, likely late 2025, as part of Starmer’s controversial push to thaw relations and win investment since his election in July.

That is despite the return of China-skeptic Donald Trump to the White House, disquiet about President Xi Jinping’s hard-nosed economic style and human rights record, and slow progress on a Whitehall-wide “audit” of U.K.-Beijing relations.

Senior government officials have complained there is no coherent approach to China — and in particular, that there is a damaging tug of war between so-called “securocrats” urging caution and the Treasury wanting to pursue a closer relationship.

Red carpet

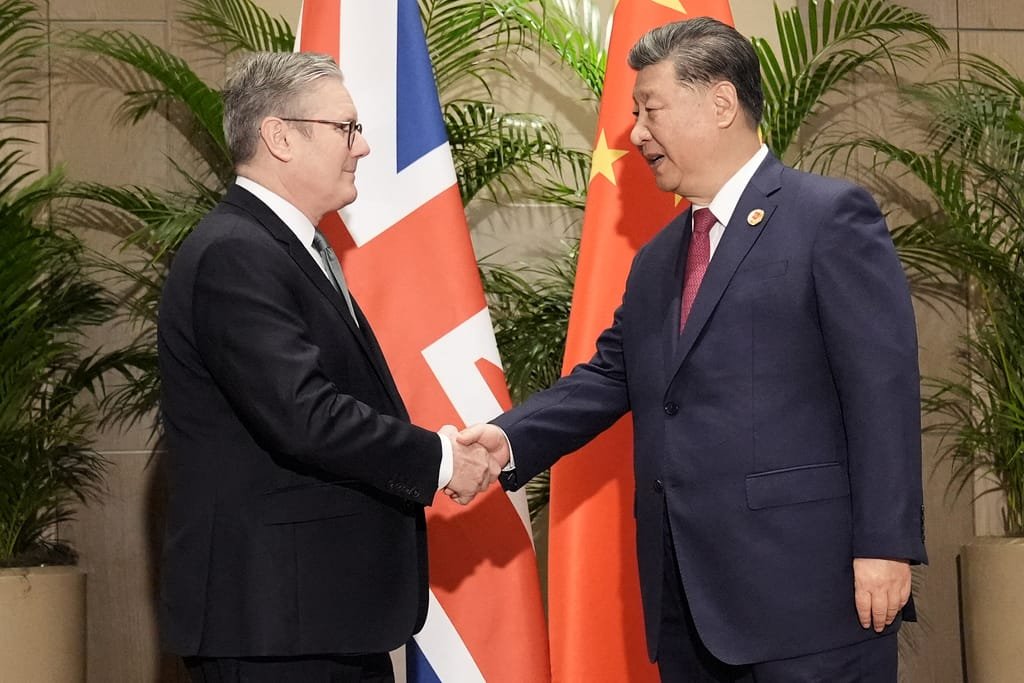

Starmer promised a “consistent, durable, respectful” relationship when he met Xi at November’s G20 summit — the first leader-level meeting in six years after relations were frozen under Britain’s Conservatives.

He said publicly then that he wanted to “plan for a full bilateral meeting” with Xi and Premier Li Qiang in London or Beijing. POLITICO reported at the time that officials were looking at a Starmer visit to Beijing later in 2025.

Those talks are now underway within No. 10 and predicated on the meeting taking place in China, said the four people mentioned above, who were granted anonymity to discuss sensitive matters. The current hope is to find a date for later this year, one of the people said.

Late spring is viewed as too soon. U.S. President Donald Trump has reportedly told aides he would like to visit China too, while Starmer — along with his campaigns-focused chief of staff Morgan McSweeney, who is facing the rise of the right wing Reform UK — is staging his foreign trips carefully after a flurry of travel last year prompted criticism at home.

More importantly, Starmer has to work out what Britain actually thinks about Beijing.

China audit goes slow

Whitehall is wading through a cross-government “audit” of U.K.-China relations that does not appear to be near completion, after plans to publish it near the start of 2025 were abandoned. Yet British policy and investment discussions with China are already flowing, with Foreign Secretary David Lammy visiting in October, Chancellor Rachel Reeves in January, and Energy Secretary Ed Miliband due to go early this year.

Officials say the audit is still due in spring — though spring can be as late as June in Whitehall-speak, and it is likely that not all of it will be made public.

Surrounding the audit is a debate about how much to prioritize Starmer’s and Reeves’ push for economic growth, which some in Whitehall fear has dominated.

One of the four people mentioned above said the audit was in “disarray” and had made little solid progress several months in. They added: “The primacy of the growth mission has basically derailed any attempt to do it how it was originally going to be done.”

Another of the four people suggested Trump’s arrival had created more nervousness: “My impression is that no one wants to put their head above the parapet, and that is what a China strategy would do.”

Director of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China Luke de Pulford, a Conservative Party member, said expectations of the audit are now “extremely low.” He added: “It’s widely acknowledged within government, within the China-watching community and among dissident groups that the China audit is a busted flush. Quite clearly, the government’s position regarding China has already been set — they want to do as much business as they can.

“This pattern of the Treasury versus everybody else — Treasury determining not just foreign policy but domestic policy when it comes to national security — is a real thing, and it’s become a real risk.”

Downing Street officials dispute this, saying they are taking a pragmatic approach and the whole point of carrying out the China audit is to balance Starmer’s goals on economic growth with national security. They also argue that Trump has not changed their approach.

Treasury officials argue the audit will be “full and comprehensive,” be rooted in Britain’s global interests and challenge China where needed.

De Pulford, however, argued even much of the “paltry” £600 million in investment trumped by Reeves after her January visit may not materialize.

He added: “We’re going into this engagement naively and blindly expecting a different result doing the same thing. The Chinese have us over a barrel and they know it, and we’re clearly indicating that we’re going to make compromises for paltry investment. That is not a good posture to go into a negotiation with the Chinese Communist Party.”

Emily Thornberry, the Labour chair of the House of Commons’ foreign affairs committee, also said security should not be forgotten in the race for investment. She told POLITICO the audit “needs to go right across government and pull together a policy that will frame our relationship with China for years to come. We must be consistent and there are many factors at play, but in my opinion, security tops them all.”

Red lines

No wonder nerves are raised about Wang’s meeting Thursday with Lammy, where the pair are due to discuss issues including security and the Russia-Ukraine war. No press conference between the pair is planned, and the U.K. Foreign Office said little before Wang’s arrival, even declining to confirm China’s statement that the pair would reopen a long-dormant “strategic dialogue.”

On China’s to-do list may be its bid to build a “mega-embassy” near the Tower of London, an asset of such importance to Beijing that Xi raised it in a phone call with Starmer. A U.K. planning inquiry is under way.

Another sensitive point will be whether Lammy raises China’s human rights record in Xinjiang province, where a crackdown on Muslim Uyghurs has prompted outcry. The Foreign Office said Lammy raised the issue when he met Wang in Beijing. The charity Amnesty said: “Lammy should be drawing serious red lines, rather than rolling out the red carpet.”

Campaigners will also be watching closely to see if China is included in the “enhanced tier” of Britain’s forthcoming Foreign Influence Registration Scheme, which will require actors for foreign powers or entities to declare their activities in the U.K. Reports that China will be excluded have prompted a backlash among China hawks.

Sophia Gaston, U.K. foreign policy lead at the security think tank ASPI, said China « is the most formidable actor we have faced. While some important progress has been made, the gap between this reality and the institutional architecture and depth of our capabilities remains startling.

“It is reasonable for us to engage with China, but we must do it in a sophisticated way. Without clear red lines and an expansive view of national resilience, Britain will find itself facing impossible choices between our most vital objectives and values.”

That is just a taste of the dilemmas that await Starmer in Beijing.

Sam Blewett and Esther Webber contributed to this report.