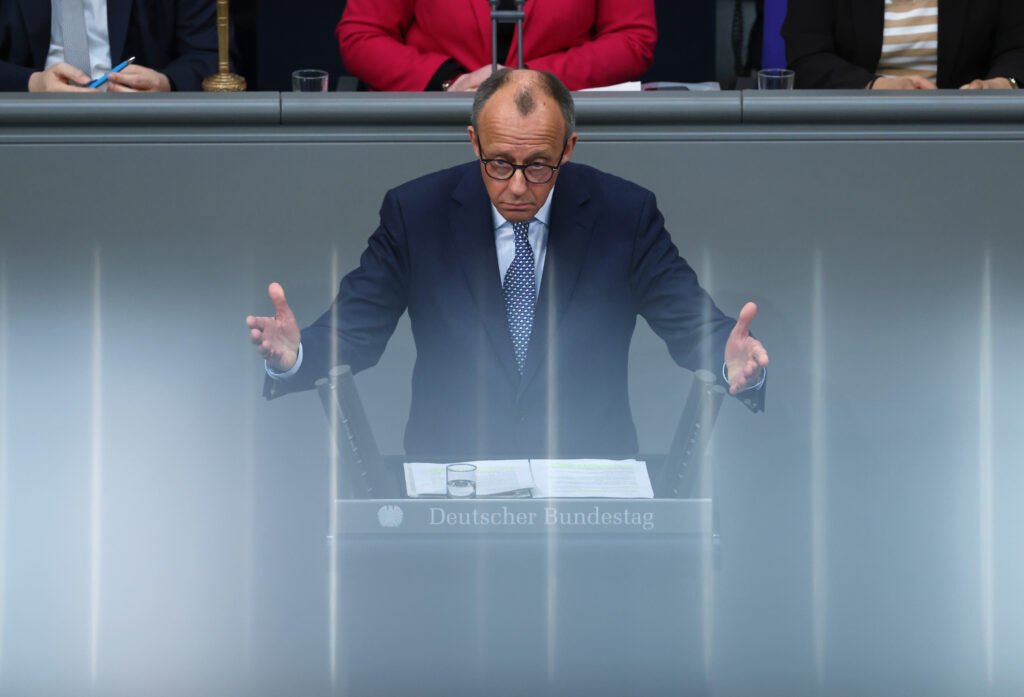

Chancellor-in-waiting Friedrich Merz is about to break years of fiscal stringency to counter the erosion of the transatlantic alliance.

BERLIN — It took a preacher of fiscal rectitude to break Germany’s near-religious belief in the wrongfulness of debt.

Just days ahead of the country’s Feb. 23 election, Friedrich Merz, the eventual conservative winner and chancellor-in-waiting, was still championing the old gospel of financial self-denial, warning that borrowing big to solve his country’s massive problems would further imperil Germany and Europe at an already precarious moment.

“We cannot be as careless with our public finances as perhaps some of the others,” Merz said in an interview with POLITICO ahead of the vote. “The next financial crisis is definitely coming.” Two days before the election, Merz declared the “end of the fantasy of all social democrats” to take on “more debt,” adding: “We’ll have to make do with the resources we have.”

Shortly after his victory, Merz began proclaiming a radically different creed, one fit for an alarming new reality in which U.S. President Donald Trump’s America could no longer be relied on to protect Europe — and could even act to harm it.

“In view of the threats to our freedom and peace on our continent,” the mantra “whatever it takes” must now apply to Europe’s defense, Merz told reporters earlier this month as he announced a historic borrowing plan that could unleash €1 trillion in new spending for defense and infrastructure over the next decade.

On Tuesday, the Bundestag, Germany’s lower house of parliament, is set to decide on a series of bills to make the plan a reality, marking some of the most consequential votes since the end of the Cold War. The bills, which will alter the country’s constitution, are set to usher in a financial sea change in the economic heart of Europe, turning the continent’s biggest economy away from more than 15 years of self-imposed austerity that have ravaged Germany’s infrastructure and hurt growth both domestically and across the continent.

Merz has justified his about-face by arguing that events abroad, namely Trump’s expressions of sympathy for Russian President Vladimir Putin and the derision he showed toward Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in the Oval Office, mean that Germany and Europe must become more independent of the U.S. on matters of defense.

“The meeting in the White House between Zelenskyy and Donald Trump really showed the whole drama in which we are living today in terms of security policy, and that is why we had to act quickly,” Merz said on public television on Sunday. “We now have to take a more independent path from America,” he added. “Europe’s time has come.”

Acting out of weakness

It’s likely that Merz, who had notably refused to exclude a reform of Germany’s strict spending rules ahead of the election, long had the rough outlines of a defense spending plan in mind.

Trump’s statements on Ukraine in recent weeks gave Merz the political cover he needed to act immediately. But the rise of political extremes and the shriveling of the political center also forced Merz to move immediately or risk an impasse during his coming chancellorship.

Merz’s conservative alliance won the election with less than 29 percent support, well short of their expectations. In the newly elected parliament, which will convene by March 25, the Kremlin-friendly, far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party and the Left party, which opposes military spending, will have the strength to block constitutional amendments to enable more defense expenditure.

In order to get his spending plan through while he still can, Merz had to make major concessions to the center-left parties he has long railed against, in effect giving them exactly what they’ve long wanted — massive, debt-fueled spending on infrastructure and climate — because he had little choice.

At the end of last week the Greens moved to support Merz’s massive spending plan after the conservative agreed to allot €100 billion toward meeting Germany’s clean-energy goals, even though he had campaigned on deprioritizing climate.

Merz also suggested that a major part of his economic stimulus plan — a €500 billion special fund to finance infrastructure projects — was largely a concession to his likely future coalition partners, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), in exchange for the party’s wider support on defense spending. The SPD has long called for such a special infrastructure fund, while Merz has argued Germany needs structural reforms to improve growth.

“If we had received an absolute majority of [votes], we would have done things differently,” Merz said in the Sunday interview. “We have a mandate to govern, but a mandate to govern together with a coalition partner, and we are now trying to bring that together.”

Death of the Swabian housewife

Germany’s puritanical streak when it comes to accruing debt runs deep. After all, the German word for “debt,” Schuld, also means “guilt.”

Germany’s debt brake, which restricts the federal deficit to 0.35 percent of GDP, was written into the constitution in 2009 during the reign of then-Chancellor Angela Merkel. Europe was at the time enmeshed in a spiraling debt crisis, and although Germany had the ability to borrow cheaply, Merkel and much of Germany’s political establishment believed it was more important to provide profligate borrowers in southern Europe with a moral paragon. Merkel invoked the frugal “Swabian housewife,” a character who had the common sense to know that every household must live within its means.

That moral attitude has long roots in the German psyche. German households in the past have often maintained high rates of savings, even when it made little financial sense. Even during periods of hyperinflation, such as the interwar Weimar Republic, when money was nearly worthless, Germans continued to save at relatively high rates, according to economic historian and curator Robert Muschalla.

“You can assume that the ideology of this savings behavior is so unconscious and deep-seated that it plays a big role in the political arena,” Muschalla said. “There is no real economic reasoning behind it, if you like, but it’s rather a truly moral consideration.”

It’s somewhat of a paradox that Merz might be the one to bring about the death of Germany’s mythological Swabian housewife. One of his political mentors, after all, was the late conservative stalwart Wolfgang Schäuble, the face of European austerity during the continent’s debt crisis.

Now, however, even conservatives who admire Schäuble view his legacy with more nuance. “I take a critical view of the years in which Schäuble was finance minister,” Günther Oettinger, a former European commissioner and longtime senior politician in Merz’s Christian Democratic Union, told POLITICO. “We clearly spent too little for the military in the budget. So Merz must now make a correction.”

Money alone

Merz is set to get the financial firepower he needs to invest heavily in Germany’s defense and economy, but that’s just the beginning of the battle.

Economists warn that big spending alone won’t solve Germany’s competitiveness problems. A recent ifo Institute survey of 205 economists showed that most viewed structural reforms such as reducing bureaucracy and reforming the tax code as more important to stimulating economic growth. The German state, many also warn, also lacks people with expertise to disburse the funds in the most effective way.

And while there’s widespread support for more defense spending to bolster Germany’s moribund military, that funding won’t magically restore Germany’s armed forces to the fighting ability they boasted during the Cold War. Despite a recruitment drive intended to grow the force, Germany’s military is shrinking and aging. That doesn’t bode well for the defense of Europe, which, according to one study by think tank Bruegel, would require hundreds of thousands of new troops to replace American protection.

In many ways, Merz has done the easy part in agreeing to spend more money with center-left parties that favor munificence. The question now is whether the money will be put to good use.

“We are now really facing the major task of reforming our state,” said Merz on Sunday. “Money alone won’t really make us successful.”